Can hiding likes make Facebook fairer and rein in fake news? The science says maybe

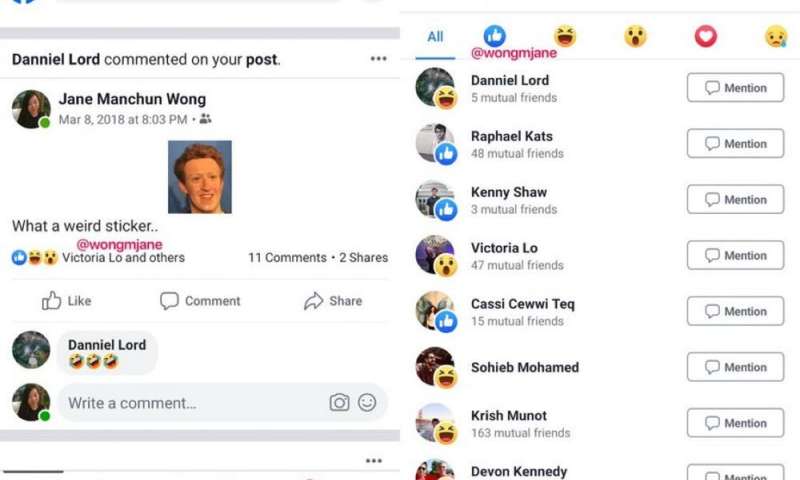

You may have read about—or already seen, depending on where you are—the latest tweak to Facebook’s interface: the disappearance of the likes counter.

Like Instagram (which it owns), Facebook is experimenting with hiding the number of likes that posts receive for users in some areas (Australia for Facebook, and Canada for Instagram).

In the new design, the number of likes is no longer shown. But with a simple click you can see who liked the post and even count them.

It seems like Facebook is going to a lot of trouble to hide a seemingly innocuous signal, especially when it is relatively easy to retrieve.

Facebook’s goal is reportedly to make people comfortable expressing themselves and to increase the quality of the content they share.

There are also claims about ameliorating user insecurity when posting, perceived liberty of expression, and circumventing the herd mentality.

But are there any scientific grounds for this change?

The MusicLab model

In 2006, US researchers Matthew Salganik, Peter Dodds and Duncan Watts set out to investigate the intriguing disconnect between quality and popularity observed in cultural markets.

They created the MusicLab experiments, in which users were presented with a choice of songs from unknown bands. Users would listen online and could choose to download songs they liked.

The users were divided into two groups: for one group, the songs were shown at random with no other information; for the other group, songs were ordered according to a social signal—the number of times each had already been downloaded—and this number was shown next to them.

A song’s number of downloads is a measure of its popularity, akin to the number of likes for Facebook posts.

The results were fascinating: when the number of downloads was shown, the song market would evolve to be highly unequal (with one song becoming vastly more popular than all the others) and unpredictable (the winning song would not be the same if the experiment were repeated).

Based on these results, Australian researchers proposed the first model (dubbed the MusicLab model) to explain how content becomes popular in cultural markets, why a few things get all the popularity and most get nothing, and (most important for us) why showing the number of downloads is so detrimental.

They theorised that the consumption of an online product (such as a song) is a two-step process: first the user clicks on it based on its appeal, then they download it based on its quality.

As it turns out, a song’s appeal is largely determined by its current popularity.If other people like something, we tend to think it’s worth taking a look at.

So how often a song will be downloaded in future depends on its current appeal, which in turn depends on its current number of downloads.

This leads to the well-known result that future popularity of a product or idea is highly dependent on its past popularity. This is also known as the “rich get richer” effect.

What does this have to do with Facebook likes?

The parallel between Facebook and the MusicLab experiment is straightforward: the songs correspond to posts, whereas downloads correspond to likes.

For a market of products such as songs, the MusicLab model implies that showing popularity means fewer cultural products of varying quality are consumed overall, and some high-quality products may go unnoticed.

But the effects are even more severe for a market of ideas, such as Facebook.The “rich get richer” effect compounds over time like interest on a mortgage.The total popularity of one idea can increase exponentially and quickly dominate the entire market.

As a result, the first idea on the market has more time to grow and has increased chances of dominating regardless of its quality (a strong first-mover advantage).

This first-mover advantage partially explains why fake news items so often dominate their debunking, and why it is so hard to replace wrong and detrimental beliefs with correct or healthier alternatives that arrive later in the game.

Despite what is sometimes claimed, the “marketplace of ideas” is no guarantee that high-quality content will become popular.

Other lines of research suggest that while quality ideas do make it to the top, it is next to impossible to predict early which ones. In other words, quality appears disconnected from popularity.

Is there any way the game can be fixed?

This seems to paint a bleak picture of online society, in which misinformation, populist ideas, and unhealthy teen challenges can freely flow through online media and capture the public’s attention.

However, the other group in the MusicLab experiment—the group who were not shown a popularity indicator—can give us hope for a solution, or at least some improvement.

The researchers reported that hiding the number of downloads led to a much fairer and more predictable market, in which popularity is more evenly distributed among a greater number of competitors and more closely correlated to quality.

So it appears that Facebook’s decision to hide the number of likes on posts could be better for everyone.

In addition to limiting pressure on post creators and reducing their levels of anxiety and envy, it might also help to create a fairer information exchange environment.

And if posters spend less time on optimising post timing and other tricks for gaming the system, we might even notice an increase in content quality.